I have always loved school. By 7 years of age I had already set my sights on an Ivy League education and on all the doors such an education would open for me. I got my first “B” in 6th grade, and feared—for a moment—that I had lost my chance to cross that hallowed threshold.

As it turns out, I graduated 2nd in my high school class, having sacrificed the Valedictorian spot to spend my junior year abroad as an Exchange Student and my senior year pursuing dual enrollment at a prestigious private college. By every modern definition I was well-educated. Or was I?

Imagine my surprise when I began to teach my own children at home, and found out that I knew next to nothing about history, geography, and science. My 10 year old is already more knowledgeable on those subjects than I was when I graduated from University.

Webster’s 1828 dictionary defines schooling as “instruction in school.” Period. I had that in spades, yet I was not well educated, at least according to Webster’s 1828 definition of that word. According to Webster, education “comprehends all that series of instruction and discipline which is intended to enlighten the understanding, correct the temper, and form the manners and habits of youth;”

The public school is enemy territory for the Christian student, and those who enter this war zone can expect to have their morality, worldview, and identity as a Christian challenged at every turn. It can hardly be said that this hostile environment enlightens the understanding, where Darwinism reigns and the standardized test score is king.

It is true that the school environment will shape a child’s temper and habits, but it is likely the child will pick up as many negative habits as positive ones. I have spent my adult life trying to undo the habits I formed in my youth, and my innately sinful temper was not corrected in that environment; instead, it fed my pride and my desire to please man.

Webster goes on to say that education should “fit them for usefulness in their future stations.” When I graduated from University I could read Chekhov in Russian and translate Faust from the German, but I could not cook a potato–much less a full meal. In spite of all my schooling I lacked the basic knowledge of many necessary skills.

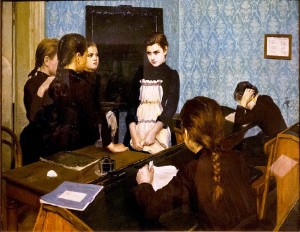

How much of our sons’ time is spent preparing them for their future stations as men of God, husbands and fathers who will one day represent Christ as the head of their families (Ephesians 5:23, ESV)? Are we fitting our daughters sufficiently for their likely long term future station as a wife and mother? I am not opposed to girls getting a college education, if that education will better prepare them to be a suitable helpmeet to their future husband.

My education gave me the confidence and the ability to write this article, and for that I am grateful. Many of us, however, have accepted the cultural default position, which tells us that our daughters are no different than our sons, and that they should prepare to be independent breadwinners, rather than homemakers.

Webster goes on to say that “to give children a good education in manners, arts and science, is important; to give them a religious education is indispensable”. I am not suggesting we neglect to instruct our children in the arts and sciences. On the contrary, our Christian children need and deserve the best education we can give them. They are the arrows we will soon launch into a pagan world, and the ones who will bring the gospel to future generations.

But Webster rightly points out that although the arts and sciences are important, a religious education is indispensable. It goes without saying that the public school is antagonistic toward a religious education. Yet even we who home school have often taken the government schools’ educational system and replicated it at home. Are we prioritizing math and grammar above the knowledge of God’s Word? Is it more important to us to raise a scholar or a disciple of Christ?

Graduating scholars from my home school may validate me in the eyes of the world, proving that the sacrifice of my time and potential career was “worth it”. But what does it profit a man—or a child—if he gains the whole world yet loses his soul (Mark 8:36 ESV)?

Webster concludes his definition of education by saying that “an immense responsibility rests on parents and guardians who neglect these duties.” First, we must remember that it is “God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (Phil. 2: 13, ESV). We cannot sanctify our children; that is the work of the Holy Spirit. Nevertheless, we are responsible before God to educate them, in every sense of that word.

We dare not merely school them.